The lovely weather we've been having here in England always makes me think of Lydia Bennet's adventures in Brighton! Here's a little taster of the fun and scrapes she experiences with her friend Harriet Forster.

The lovely weather we've been having here in England always makes me think of Lydia Bennet's adventures in Brighton! Here's a little taster of the fun and scrapes she experiences with her friend Harriet Forster.Lydia and Harriet were dressed and downstairs by seven o’clock next morning to go bathing. They left the Colonel snoring away, as he was not due to inspect his troops till one o’clock, and hastened down to the beach to be dipped by Martha Gunn and her ladies. The girls decided to share a bathing machine for changing, but as there was hardly any room to manoeuvre, they kept falling over, partly because of the necessity of standing on one leg to undress and partly because they were laughing so much. Once they had on their flannel gowns and caps, it was time to face Martha Gunn, chief dipper and a woman not to be opposed. She stood in the water whilst her servant and helper led them hand in hand down the steps, but as soon as they hesitated with a first toe in the freezing water, she stepped up and very firmly took charge. She was a strong woman, and before they realised what was happening, they were submerged. Lydia would never forget that first occasion. She declared the horror of it would stay with her forever. Such was her surprise at being forcibly plunged into the icy brine, she forgot to hold her nose as instructed and as she emerged, coughing, feeling half drowned, she was convinced she had drunk several day’s dosage of the recommended amount.

“I cannot imagine any circumstance where I would be induced to try this heinous activity again, unless I was desirous of drowning myself and anxious to have done with my life,” she spluttered.

“I cannot agree, Lydia,” Harriet declared, splashing her friend till she shrieked for mercy. “I find it most refreshing and invigorating, and I profess that the water is exactly the temperature I prefer.”

“You are clearly most insensible, my friend. I always knew that, of the two of us, I was the most sound of mind and feeling,” shouted Lydia, as she escaped another assault and ascended the steps, dripping and cold.

Getting dried, dressed, and changed into one’s clothes, not to mention trying to dress one’s hair so as not to appear a complete fright, was a skill which they had not yet mastered after sea bathing. They almost ran back to the inn, which fortunately was opposite the steps they had descended, but as they reached the summit and were stepping out to cross the thoroughfare, they were intercepted by a curricle which swerved, making the horse rear, forcing Harriet to fall backwards, sending Lydia reeling to the ground. As she recovered herself, she saw that the driver had at least had the courtesy to stop, but she could have died as she slowly recognised the buff and blue livery of his servant, the buff and blue paint of his carriage, and, finally, the blue cloth of his coat, his buff breeches, and cockaded hat, a picture of perfection and in great contrast to the one which the girls presented.

Lydia scrambled to her feet, aware not only of her unkempt hair poking under her bonnet but of her general appearance of dishevelment, now that her white muslin was covered in grime and dust. She bit her lower lip, tasting the salt encrusted there, and cast her eyes down to the floor in the vain hope that he would not recognise them.

“Dear ladies,” Captain Trayton-Camfield declared, leaping to the floor and bowing before them, “forgive me, I did not see you. I hope you are well. Please tell me that you are not injured at all, for I shall never forgive myself if you are harmed in any way.”

“Please, sir, do not be alarmed, and thank you for your concern,” said Harriet, “but we are just returned from a little sea bathing, and I am afraid that in our haste to return to our inn, we did not see you.”

“Would you allow me to insist that you rest awhile in my chariot or may I escort you to a safe haven? Are you staying near? Please let me take you to your home,” the Captain entreated.

“Sir,” replied Harriet, “we are entirely at fault. It is we who should be apologising to you, sir. Pray, do be easy; we are not harmed in any way, though a touch shaken, to be sure, but nothing that a little rest in our rooms over the way will not cure.” Harriet brushed at Lydia’s gown and thrust her forward.

Captain Trayton-Camfield looked across to the Ship Inn. “I should have known that two such genteel ladies would be accommodated in refined surroundings. Please, may I beg your permission to introduce myself. I insist that it is quite the thing in Brighton to dispense with the formality of waiting for Mr Wade to perform the introductions! Indeed, I feel I know you already as I never forget a pretty face; haven’t we already met on the Brighton Road?”

Lydia was inclined to giggle at his forthrightness. I must admit, I like his open manner, she thought. But Harriet had suddenly become more than a little reticent in her replies. She clearly thought the Captain was overstepping the bounds of propriety and was keen to make her escape. She dismissed him as politely as she could; he took his leave, jumped onto his seat, and with a wave of his hat, cantered off in the direction of the Marine Parade.

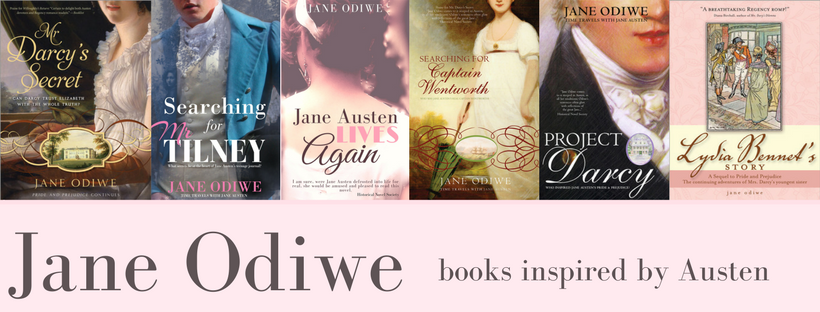

Extract from Lydia Bennet's Story published by Sourcebooks Copyright Jane Odiwe

From the My Brighton and Hove website

As the popularity of sea-bathing grew so a new profession developed, with some of the town's fishermen and their families turning to bathing visitors for a living. Ladies were bathed by so-called 'dippers' and gentlemen by 'bathers'; in both cases the subject was plunged vigorously into and out of the water by the bather or dipper.

By 1790 there were about twenty dippers and bathers at Brighton and they continued in business until about the 1850s. The 'queen' of the Brighton dippers was the famous Martha Gunn. Born in 1726, she was a large, rotund woman and dipped from around 1750 until she was forced to retire through ill health in about 1814.

She was a great favourite of the Prince of Wales who granted her free access to his kitchens; an amusing story relates how she was given some butter on one of her visits, but was cornered by the Prince who continued talking to her while edging her nearer the fire until the butter was running out of the poor lady's clothes.

Martha died on 2 May 1815 and is buried by the south-eastern corner of St Nicholas Church.

The portrait above was donated by one of her descendants to the Brighton and Hove Museum.